‘What’s that smell, Jeff?’ a woman asks from her doorway in an apartment corridor. ‘Oh, uh…I really like cooking pork chops.’ This is one of a string of unlikely explanations Jeffrey Dahmer gives his neighbour for the horrid stench emanating from his apartment. Presumably if you’re watching Netflix’s true-crime drama about the serial killer Jeffrey Dahmer, you know the smell isn’t pork chops.

Criticism so far of Dahmer—Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story, apart from the fact it says Dahmer twice in the title, has focused on its insensitivity to the victims and the sensationalising of the man’s hideous crimes. The first episode was neither of those things—indeed I was struck by its slow thoughtfulness and careful portrayal of what are famously real-life events.

The first episode opens with the eerie, muffled sound of a power drill drifting through the neighbour woman’s air vent. She sits in front of the television, which she has muted to listen to the disturbing noises next door, and quietly weeps. The camera pans upwards and through the air vent to the other side where Jeffrey Dahmer cleans blood off his hands and tools. The camera doesn’t show his face, only his middle. Already this show is telling us it will focus on the heinous acts he did with his hands—and it won’t shy away from it.

There is a fine line between depicting real-life killings, and revelling in them. This show does the former. I was immediately impressed at the emphasis given to the neighbour woman Glenda, who frames the first episode by appearing at the beginning and end, telling the police as they arrest Jeffrey, ‘I called you, I told you over and over, a billion times, ya’ll did nothing.’ She is the first person we see on screen and we know she is going to be deeply affected by the experience of living next to Jeffrey Dahmer.

This isn’t just a story about a serial killer—it’s also about the people whose lives he affected, and not only his victims and their families. The show is really asking how these crimes can happen over a prolonged period of time, especially in a crowded apartment building.

Part of the answer is that the authorities—primarily white male cops in Milwaukee, Wisconsin— didn’t take seriously the reports of missing young gay black men, or the pleas of a black woman residing next door to Dahmer’s apartment. But the white male policemen aren’t portrayed as racist monsters. A bit thick, yes, and complacent, and partly to blame for why so many young men went missing. The two policemen we see in the first episode aren’t portrayed as straightforward villains though. Initially suspicious of the black man Tracy Edwards, who has come running down the street, half-naked and handcuffed, shouting for the police, they do listen to him and follow him to the apartment where they discover the evidence of Dahmer’s horrific crimes.

Dahmer—Monster is admirably accurate and for this it should be considered sensitive to the victims and their families. How much more offensive would it be to portray their story and make it more sensational, rather than staring the events in the face and presenting them as they happened? Depicting such events isn’t sensationalising them. It’s telling a true story. That’s what’s so unnerving about the story of Jeffrey Dahmer—it feels like it should come out of an 80s horror film or a Stephen King novel, but the truth is as horrific as any human imagination can invent.

The GQ magazine film critic complains that the show seems to ‘relish in [Dahmer’s] barbarism’, lingering on the murder scenes and letting the cat-and-mouse tussle play out for twenty minutes or more. There is nothing gratuitous about it—it is straightforwardly depicting what really happened to Tracy Edwards on the night Dahmer tried to kill him. The slow pace of the first episode is a result of it playing out in real time. Twenty minutes is about how long it took for Tracy to realise that Dahmer was going to kill him. GQ calls this slow pace a result of ‘[director] Ryan Murphy’s intent to make our guts churn.’ If that is a result, it understandably goes with the territory—but that is not the only thing we’re meant to feel when watching a show like this. It’s gruesome, yes and disturbing. I don’t watch it at night. But there is a point to such a drama and it’s doing it a disservice to say it exists only to make us cringe.

Critics at GQ and the Telegraph, that say Dahmer—Monster ‘sets itself the challenge of being entirely unwatchable’, could be criticising the entire true-crime and horror genre, and many are. Why would anyone want to watch it? they ask— what does it say about us humans that we consume this stuff for entertainment? Well, it says that we humans are interested in other humans, especially the ones on the extremity. We are curious, vulnerable and (most of us) aware that evil does exist in the world. Telling stories about evil and the forms it takes in other people is not a shameful thing. It’s natural, and actually quite healthy. We tell ourselves these stories partly for catharsis—to process horrific things that have happened to us in some cases, or simply to meditate on the grim realisation that these things can and do happen to other people, and could to us.

Many people, top critics at Variety, Telegraph and GQ among them, simply don’t want to watch this kind of thing, and that’s fair enough. But reviewing it poorly because you don’t like the entire genre is thoughtless and unfair. If you don’t want to watch it, don’t watch it. But it would be unwise to dismiss the justifiable interest many people have in stories of serial killers.

Dahmer— Monster remarkably invokes pity for such an evil man. In the first episode he goes out to a gay club and hits on three men at the bar, all at once. ‘You hit on me last week,’ says one. ‘Me too.’ Dahmer has so little understanding of how to connect with other people that he doesn’t even recognise the men he met the previous week. His attempts at conversation are embarrassing and we can see he’s made fun of wherever he goes. His is a pitiful existence. He also doesn’t seem to make much effort to disguise what he’s doing. He keeps his bloody power tools and a 57-gallon tub of acid and decomposing bodies in his bedroom. It’s as if he’s incapable of seeing things from other people’s perspective. A monster indeed, and one to be studied to increase our understanding of how such people come about. Dahmer— Monster does just that, and the result is a sober contemplation of how these events took place.

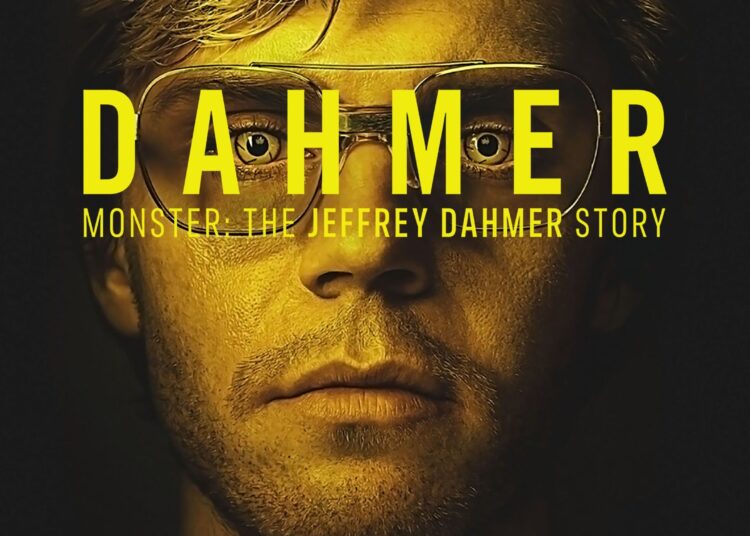

Feature image: Netflix

Check out more Entertainment Now TV news, reviews and interviews here.