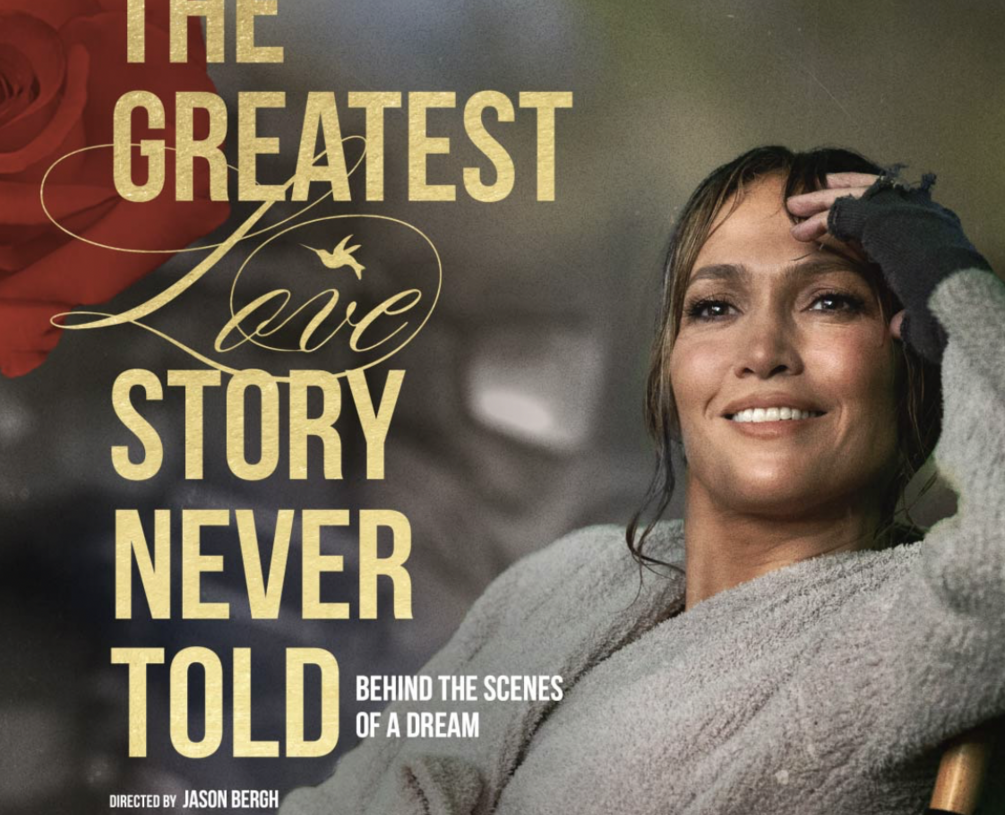

Alongside her ninth studio album, This Is Me…Now, Jennifer Lopez has released two feature-length films this month. And no, they are not music videos. They are a 20-million-dollar ‘love letter to herself’: The Greatest Love Story Never Told and This is Me…Now: A Love Story. The fact that there are two films confused me. I wanted to watch the documentary about the making of the film, but I couldn’t distinguish it from the actual film, the one the documentary was about. I finally figured out the difference between watching the documentary and not the film because I couldn’t bear to watch J Lo attempt to tell a coherent story in an actual film, which is essentially a sixty-five-minute long music video, even though the creative team insists it isn’t.

In The Greatest Love Story Never Told J Lo brings us behind the scenes to watch her put together a film about her relationships. After four marriages Lopez feels the need to explain what’s gone down in her private life. ‘You really don’t have to’, says her fourth husband Ben Affleck.

Of course, he doesn’t want a full-length film about Jennifer’s private life, it’s his private life too. And it’s messy. Also as Ben points out, if you tell the story then it’s not the greatest story ever told. His sardonic comments in the documentary do nothing to convince us that J Lo has finally found a loving, respectful partner. If you’ve ever seen Ben Affleck’s interview during his Batman promotional tour, you’ll have a less than favourable impression of the man. No one else seems to want J Lo to embark on this project either—even people like her manager, who might stand to gain from it. A studio signed on to fund it dropped out. All the celebrities she called to ask if they’d appear in the film said no. Normally this would mean the bin for a project, but J Lo went right ahead and did it herself.

Self-funded films are the kiss of death in Hollywood, and so are long-form music videos. This is why her manager insists that this project isn’t a long-form music video. They don’t sell. Rihanna has tried it, and Beyoncé has tried it. But J Lo doesn’t care. It’s not a commercial venture.

It’s art, the purest kind—the compulsion to visually express something one feels inside. And no I’m not being sardonic. The one admirable thing about this pair of films is that they come from the compulsion to make art for its own sake. They’re not good films, but she has succeeded in convincing us that they’re not a money-making enterprise. They are as earnest as Hollywood gets. There is the odd predictable behind-the-scenes glimpse of Lopez weeping, having lost all confidence in the massive task she’s undertaken, followed by inspirational music and the steely glint of determination in her eye. But it’s all her.

No studio execs steering her towards a more commercial outcome. She put twenty million dollars of her own money into it.

No wonder Ben Affleck was nervous.

As part of her inspiration, J Lo brought out the memory album of her and Affleck’s love letters to each other throughout the years—every single one of them—and showed it to her creative team. It’s pretty uncomfortable to watch Affleck talk about it on camera. He hates it but he wants to support his wife in her creative project. By bearing all, J Lo hopes the world will see how true and deep their love is. But why do we all need to know? The journey J Lo is actually on is the pursuit of true self-love.

That’s what the greatest love story is about—love for herself. There’s even a sequence in This is Me…Now with J Lo and a little girl playing her younger self. They both cry and older J Lo gives young J Lo a hug, and Young J Lo then crumbles into rose petals and flies away on the wind. It’s embarrassing to watch, but it also somehow works as a metaphor for letting go of past pain, of ‘the little girl’ inside us grown women who didn’t have the voice to speak up for ourselves.

A less successful metaphor involves the film’s tedious ‘heart factory’ sequences. In these, J Lo is a hard-bitten sweaty, sexy factory worker in a warehouse filled with other sweaty sexy women, some of whom tend to the delicate flowers growing in long rows on the shop floor. Other sexy women like J Lo tend to the throbbing chrome engine at the centre of it all, which is the heart. But the heart is breaking—sparks fly and suspension ropes snap, leaving the machine hanging precariously above the ground. For some reason mud pours out of great pipes, blasting the workers as they attempt to flee the danger zone.

Sexy J Lo rescues one woman who’s slipped on the mud, then jumps on a swinging wrecking ball to sing the main chorus line: ‘ It ain’t hearts and flowers,/It ain’t all hearts and flowers,/ Before you see my life and say I live the dream,/ Remember everything ain’t always what it seems. What she’s trying to say is that her life isn’t rosy, even though she has $20 million to spend on a vanity project. And that’s a perfectly reasonable message for a Hollywood autobiography.

I’m sure many stars feel that their lives look picture-perfect, but actually they’re human and having a hard time. The confusing thing is that hearts and flowers are the metaphor for her life, the physical expression of the beauty within. So surely it is all hearts and flowers.

There are other more convincing metaphors, and usually when she lets loose on the dancefloor. In one sequence she is tied in an elastic band to an abusive partner, forever bouncing back into his arms each time she tries to escape. That one makes sense. And boy is she a good dancer. She throws her ageing body into the same kind of gruelling choreography she did as a twenty-year-old—and she’s fifty-four.

Finally, at the end of the documentary, J Lo gets the news that her films have been bought by a major studio. Good for her. Now maybe she can sit down on the couch and scroll through Netflix like all the rest of the world’s fifty-four-year-olds.