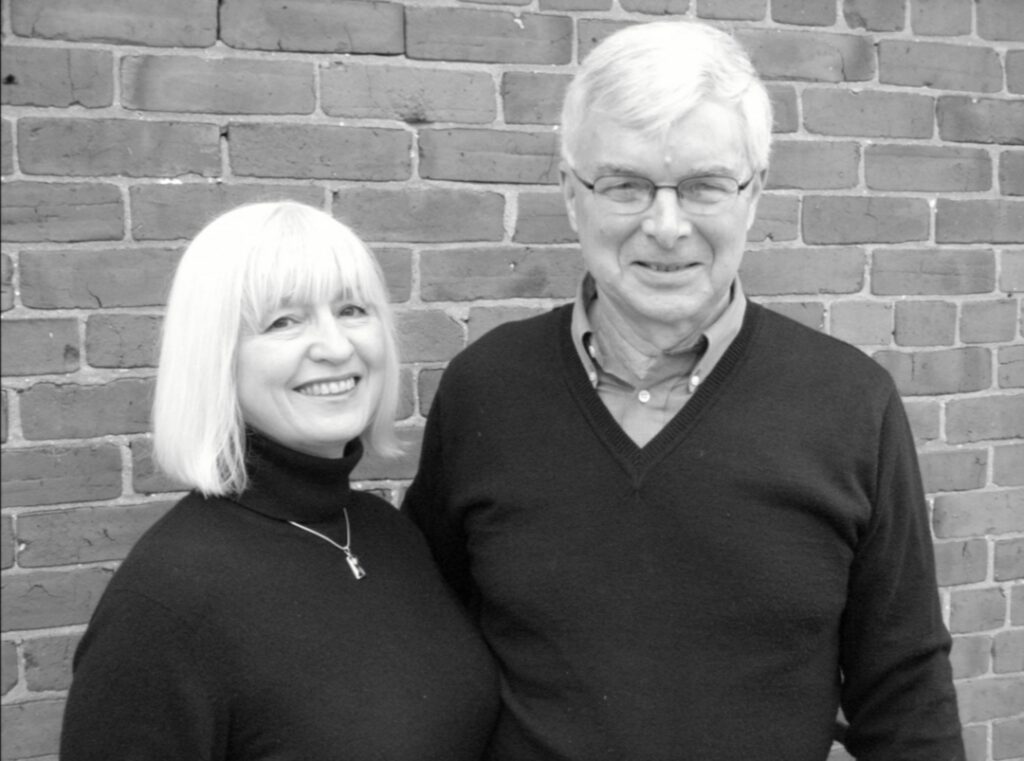

From the editors of Nella Last’s Peace, social historians Patricia and Robert Malcolmson release a new publication today (21 July). A Nurse’s War follows the life of Kathleen Johnstone, a young nurse in 1943 who documented three years of day-to-day life during conflict.

Exclusively for Entertainment Now, Patricia and Robert offer a written piece giving a comprehensive insight into what to expect from their new release today…

A Diarist in Wartime

By Patricia & Robert Malcolmson

In late August 1939, with talk of war almost everywhere, the social research organization Mass Observation (MO) invited Individual Britons to keep a “Crisis Diary”. A few days later, on 3 September, war was indeed declared; these diarists and in due course many others took to recording their experiences of life on the home front, their daily activities, and what they observed as they went about their normal (or sometimes abnormal) routines. A total of around 480 people became MO diarists between 1939 and 1945, though many gave up after a short while. Some people, though, wrote for years and a few proved to be very adept as writers and “Observers”. The testimony they left reveals a huge range of wartime experiences and attitudes to life and death.

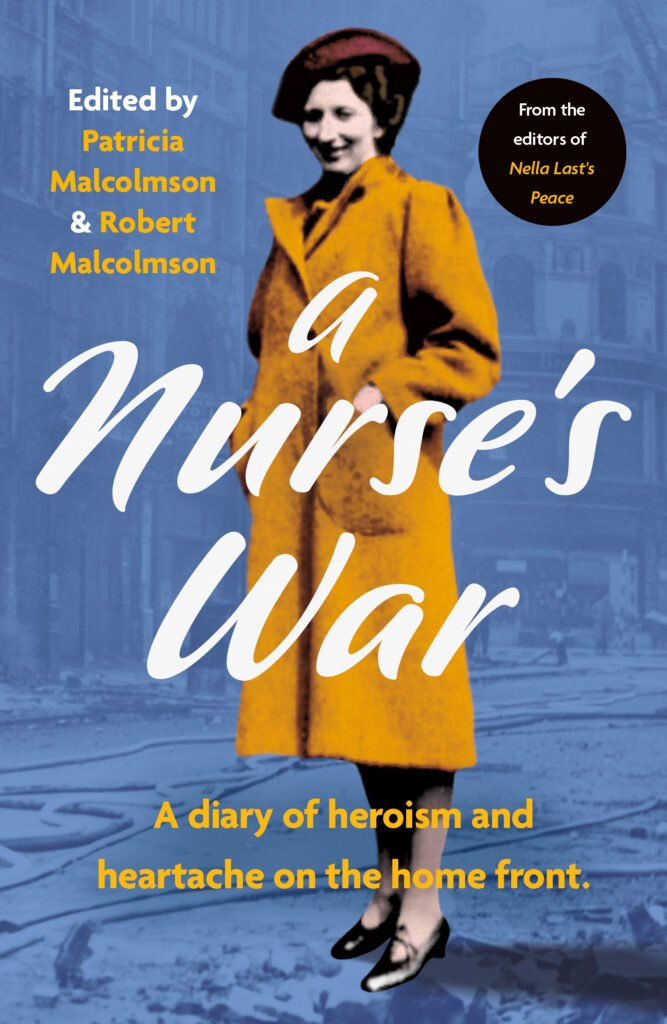

One of these stand-out diarists was Kathleen Johnstone (b. 1913), who started her diary in June 1943 and continued to write after the war, until September 1946. Our edition of her wartime writing has just been published as A Nurse’s War: A diary of hope and heartache on the home front (HarperNorth). Kathleen was initially a nurse-in-training and later state registered nurse at the Blackburn Royal Infirmary in Lancashire, a voluntary hospital that was supported by private donations; about half of the funding came from the region’s working class. During her days off work – in Blackburn she lived in the hospital’s “Nurses’ Home” – Kathleen usually stayed with her parents in their tied house in the beautiful village of Downham, near Clitheroe. Almost every day for over three years she conscientiously kept to her diary-writing, wherever she was, whether on the night or day shift, whether happy or sad, whether mostly alone or with family or friends, leaving a vivid record of the diversity of one young woman’s wartime life.

By the time Kathleen Johnstone started her diary it was clear to most people that Britain would not be invaded, as had been feared in 1940-41, and that she and the Allied nations would be in some sense victorious. But what was victory likely to mean? Would it happen soon or only years down the road? Would the Germans – those mighty warriors – make some sort of comeback? What destructive tricks might Hitler have up his sleeve? Who could say what to expect? Perhaps for many citizens in 1943-44, the most important question was – how many men would die before war ended? And who amongst one’s friends and loved ones and acquaintances would, during these months or years, go to their graves? Life during the last two years of war – and we only know this “lastness” from hindsight – was awash in uncertainties.

Kathleen’s diary is rich in reporting these uncertainties. Her younger brother, in the Army, is awaiting a posting abroad and in late 1944 is sent to the Far East. Her mother’s health is at least a little wobbly, for she is feeling the consequences of wartime trials and tasks, including the many volunteer activities (the Women’s Institute and others) to which she was actively committed, as were many women in wartime. Kathleen is delighted with the progress of British and American forces in the summer of 1944, but then there are setbacks in the Low Countries at the end of the year, and morale slumps briefly. As for her own future, little is clear. She dreads her nursing exams scheduled for the autumn of 1944; and even if she passes them (she’s sure she won’t), she wonders what kind of postwar nursing career will be open to her.

Most importantly, there is uncertainty about the life of Bill, her POW boyfriend and later fiancé in Germany, whom she hasn’t seen since October 1939. She’s been loyal to him, and apparently resisted the overtures of other men. But will their planned marriage ever come off? Will he survive his ordeals? If he returns, how changed will he be? She feels that she’s changed a lot, and become much more independent. The last message from him reaches her in February 1945, and as the war winds down and Allied POWs start coming home, she watches anxiously for his reappearance.

Along with all these wartime realities was everyday routine, the normal life of work and some play and the reality of being connected to others in a variety of ways. Kathleen is working at a major hospital and a lot goes on there. Babies are born and sick infants are treated. Some patients come for just a few days; others come to die. Death is an inevitable part of hospital life; nurses can’t afford to be sentimental about victims. Stoicism, annoyance, relief, excitement, serenity, frustration – all these appear in different passages of Kathleen’s diary. When in August 1944 a group of injured German soldiers and SS men arrives for treatment, there is consternation among many of the staff, even uproar. Polish patients are enraged; a foreign doctor, whose family has been murdered by the Nazis, refuses to treat the wounded enemy. Probably the most shocking deaths for Kathleen are those in normally tranquil Downham in January 1945, when a murder-suicide extinguishes the five lives of a whole family. The motives of the killer, husband and father and respected member of the community, were unfathomable.

But Kathleen’s diary is by no means all grim. Life, even in wartime, had its pleasures. There were dances to attend (when nurses were invited out Matron warned them to behave themselves), country walks to enjoy, coffee to be sipped in cafes, jokes to be shared, books to be read, friends to shop with, a visit to the cinema to look forward to. She writes of April Fool’s Day – a neophyte might be sent in search of the Grave Digger’s Journal; and VE-Day was marked by raucous celebrations, which included making bonfires of the plywood that had blacked out hospital windows. The hospital authorities were displeased with this destruction of government property. Kathleen takes pleasure in bending or breaking some of the petty hospital rules and regulations, and some of her writing displays a lightness of touch and ironic outlook on herself and others. Yes, living was often a serious matter and perils of some sort were pretty much everywhere (though few bombs fell on East Lancashire), but it was best not to let the mind wallow in bleakness, for there was, at the least, some fun to be had and events to enjoy and odd human behaviour to laugh at.

A Nurse’s War is, then, a book that testifies to the range of experience in wartime, and shows how much can be learned from the writing of a woman who is thoughtful and self-aware and adept at putting into words her observations of the many public incidents and private moments that made up her every-varying life.

A Nurse’s War edited by Patricia and Robert Malcolmson is published by HarperNorth on the 21st July.

* * * *

Check out more Entertainment Now lifestyle news, reviews and interviews here.