An invitation to understand the driving forces behind perceptions of beauty, Tia Byer examines the Wellcome Collection’s thought-provoking exhibit.

The Wellcome Collection is a museum that explores health and human experience. With a vision to challenge the way we think about and feel about human health, by interweaving narratives from science, medicine and art, The Wellcome Collection offers up an exciting showcase with its latest exhibition The Cult of Beauty.

Ideas and ideals of beauty have existed in every era and every culture. Beauty is seen as something to strive for, a form of perfection that artists seek to capture, philosophers look to define, and scientists innovate to achieve.

Beauty is a myth, as poetic as it is scientifically engineered, an unattainability and commodity so closely linked to our sense of health and well-being that it becomes worshipped in an almost cult-like fashion.

Featuring creative artworks, historical artefacts, films and brand-new commissions, The Cult of Beauty exhibit traces the impact of gender, age, race, morality and status on the notions of what it means to be beautiful. The exhibition celebrates and questions notions of physical attractiveness and how they shift over time.

Classical Beauty

The question of how beauty is constructed can be found in classical art. Indeed, classical sculptures, designed with strict rules of proportion, were once recognised as the epitome of the human form.

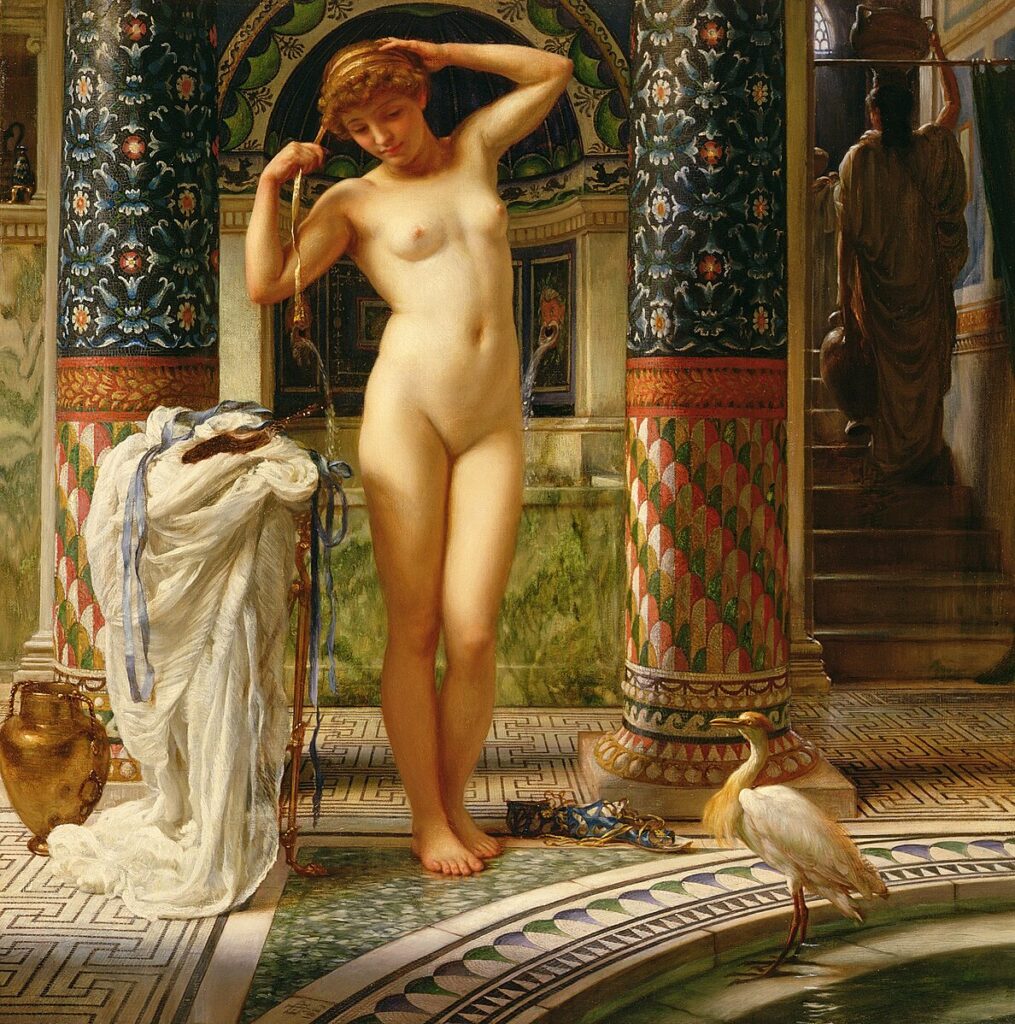

Dating back to the 500s BCE the classical style depicts the singular perfect female and male figure. Its influence continued in the 19th century and its artistic trends. When The Esquiline Venus (pictured above) was discovered in 1874 and put on display at the Capitoline Museum in Rome, a resurgence of appreciation took hold.

1919), Diadumenè ; painted 1883.

A generation of Victorian artists called the ‘Olympians’ became so enamoured by the classical style they sought to bring to life the original depiction of the goddess of love and beauty first constructed by Athenian sculptor, Praxiteles in the fourth century BCE. In 1883, Edward John Poynter reimagined the mythic Venus, painting her in colour and this time with arms.

This sense of reality brought to the unreal while shocking some audiences, set a clear standard for what female physicality should look like: pert, hairless, and eternally youthful.

Imperfection in Beauty

At the other end of the spectrum sits imperfection in beauty. Beauty tools such as make-up and skin ointments were first developed as medical devices. However, as the scientific age approached and tastes in appearance changed, so too did perceptions of good health.

A Harlot’s Progress ; engraved

Beauty patches for example, or mouches (meaning ‘flies’ in French), date back to the 1640s and were commonly worn by both sexes to strategically cover smallpox or syphilis scars. Sex workers especially wore them to attract their clientele, hiding their often marked skin.

However, by the late 17th and early 18th century, beauty patches transformed into elite accessories, worn to enhance radiance and emphasise the whiteness of skin. They also became a social tool, where the placement of your mouche could suggest flirtatious intention and even political allegiance.

The popularity of mouches waned with the advent of the smallpox vaccine in 1796.

Beauty Sensorium

The highlight of the exhibition is a multi-sensory installation exploring 16th-century skin and haircare recipes. Designed the art studio Baum & Leahy and based on research by the Renaissance Goo project at the University of Edinburgh, the project is funded by the Royal Society.

This ceramics installation and beauty sensorium showcase five reconstructed recipes from Renaissance apothecaries. With an accompanying ASMR soundscape – think bubbling potions noises – and scents of rosewater, willow, and musk, the tactile encounter invites visitors to understand how the pioneering chemists of the past influenced the workings of soft matter scientists of today.

The Cult of Beauty at the Wellcome Collection is an informative and worthwhile exhibition. Instead of providing a chronological overview of the concept of beauty and how its meaning has changed over time, the exhibition brings different contexts and formats into dialogue with each other.

What’s more, The Cult of Beauty encourages visitors to reclaim agency over identity and define beauty according to their own values. A liberating experience if ever there was one.